by Bruce J. MacFadden (@bmacfadden)

The FOSSIL Project officially began in 2013 with the submission of a proposal to the National Science Foundation (NSF). Back then we did not fully understand where it would lead over the next six years and all of the positive outcomes that have happened during this interval. Our original intent was to develop an online learning network, or what is called a “community of practice” (CoP), that would link fossil clubs, other interested individuals, and professional paleontologists throughout the U.S. We had no idea how successful this was going to be, and how it would effectively address some of the challenges of building this kind of network.

In February of 2014, after receiving funding from the NSF, we invited representatives of fossil clubs to join us at the 10th North American Paleontological Convention (NAPC) in Gainesville, FL (Fig. 1). For many members of fossil clubs, this was their first professional scientific meeting. For some (but not all) professionals, this was one of the few times that they attended a meeting with so many amateur participants. Since that time, many of our fossil club members and other amateurs have not just attended other professional meetings, but also have delivered either posters or talks from the podium. The FOSSIL Project has encouraged this practice, and in so doing, made these meetings hopefully more inclusive.

Project-supported field trips have been important to, and an essential element of the FOSSIL community. In partnership with local fossil clubs and related organizations (including the Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club, Dry Dredgers, Dallas Paleontological Society, and Special Friends of the Aurora Fossil Museum), we sponsored numerous field trips during the project. These have been special opportunities for us to share knowledge, socialize, and do what we all like to do—get in the field and collect fossils.

In addition to face-to-face meetings and field trips, it was clear from the beginning that the FOSSIL website would be the glue that held the project together. University of Florida science education professor (and Co-principal Investigator) Kent Crippen, however, had a greater vision—he saw “myFOSSIL” as a portal to understanding how people learn in online CoPs. The National Science Foundation is interested in the generation of new knowledge about how people learn in these connected communities, and how such knowledge “advances the field” of Informal STEM (Science) Learning. Accordingly, the myFOSSIL website and related concepts (e.g., social media) were developed to help our team study learning within the context of “social paleontology.” Following a formalized research protocol (approved by UF), new participants on the website could consent to participate in this study, and provide important data on who makes up the myFOSSIL community. These data have been, and will continue to be, vital to learning research outcomes of the FOSSIL project.

In addition to conducting research, NSF also expected us to disseminate our learning research findings to our colleagues and other stakeholders. This was done through more than 45 presentations (including talks, panel discussions, and via posters) at conferences and fossil club meetings. The presenters included not just the project team, but also members of our CoP. Our team has also published, or has in press, almost 10 refereed papers in professional scientific journals; more are in the works. The FOSSIL project also was an example of “Broader Impacts” in my recent book with the same title published by Cambridge University Press. Our number of active participants on the website is approaching 2,000 and grows every day. It is gratifying to see new members connecting from clubs, individually, and internationally as well. The big story, however, is the impact of social media in building this community, as is discussed below.

Our NSF project has been chronicled by more than two dozen newsletters, the last of which is being sent to you now with this article. These newsletters serve as evidence of the activities of FOSSIL and our stakeholders, and provide lots of relevant content. More so than anyone, Dr. Shari Ellis has been the person in charge of making the newsletter viable. She has, however, also benefitted greatly from the contributions of stakeholders and the FOSSIL support team. All of the newsletters are archived on the myFOSSIL website and constitute a historical archive of this project.

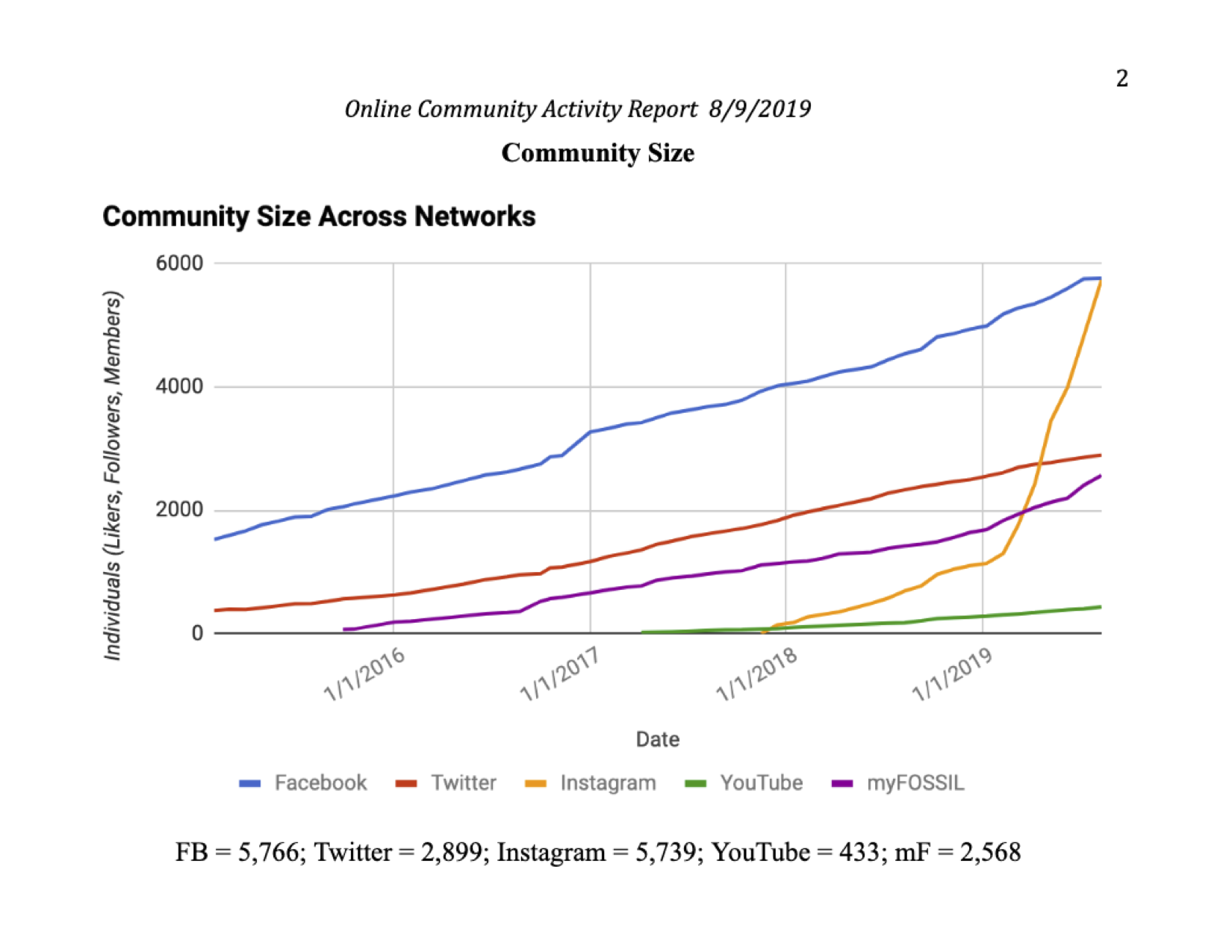

I never envisioned the extent to which social media would have an impact on building the myFOSSIL community. To say that I am social media-challenged is an understatement. It has formed a cornerstone of the project, not only as the core research done by Lisa Lundgren for her PhD, but also for all of the other users who understand its value as a communication and engagement tool far better than I do. Of our approximately 10,000 members of our myFOSSIL CoP, more than three quarters of them reach us through social media, which primarily has been through Facebook and Twitter. However, two years ago we decided to experiment with Instagram because other studies had indicated that this platform tends to engage a younger audience, one that we still wanted to attract. The rate of growth in the myFOSSIL Instagram account has been nothing less than amazing (Fig. 2); in this time it has eclipsed our Twitter and Facebook followers and continues to attract active engagement. Research on the FOSSIL community using “network analysis” continues with Dr. Crippen and his students.

In 2017 we submitted a request for supplemental funds to develop a myFOSSIL mobile app (Fig. 3) to promote public engagement in science though active uploading of fossils discoveries, including photos and associated locality data. In so doing, participants collect the same data as do scientists, thereby learning the nature (process) of science. The app links directly to the myFOSSIL eMuseum (mFeM) on our website (Fig. 4), which includes an online catalog of fossil discoveries made by our community. These observations are curated by a team of volunteer curators. Specimens that include enough descriptive data to be deemed scientifically valuable are considered “research grade,” and are being readied for aggregation by “big data” providers such as iDigBio and GBIF. With this innovation, our paleontological community is contributing to big data, which is a field of science that is currently expanding rapidly and is the wave of the future. NSF had hoped (and expected) that we would find a way to use the FOSSIL Project as a platform for learning about big data contributions to science, and through the myFOSSIL app and eMuseum (mFeM), this is becoming a reality. We are also pleased that the app and website are sustainable components of the FOSSIL Project that will be supported until at least 2022.

As with any large project, there are many lessons learned. There were some things that did not work quite so well, or that became of lower priority; three of these are described here: (1) With regard to the latter, early on we developed a “listserv” to communicate to our members. With the advent of social media, however, the listserv became obsolete and we no longer use it. (2) In another lesson learned, we invested lots of effort in developing a series of evening webinars to provide additional content for the members. These were of limited success, attendance dwindled, and were further thwarted by the video technology that oftentimes caused technical problems at the beginning of the webinars. (3) We initially tried to drive membership from social media to participation on the website; this turned out to be unrealistic and we have since understood that the CoP is composed of members connecting with us in different ways. In addition, we heard repeatedly that many fossil clubs were not bringing in the younger generation into the club activities, and they are concerned about the future as a result of this kind of engagement. Based on our demographic data, we are seeing a larger engagement from younger participants through the myFOSSIL app and the explosive growth of Instagram (Fig. 2 above).

When all is said and done, and the data and metrics are collected and analyzed, it all comes down to the hard work of people who are committed to a common goal of learning about, and contributing to, paleontology through their love of fossils. But this does not just happen. There are so many people to thank. First and foremost, without the interest and support of the amateur community, the FOSSIL Project would have faltered. The amateur community quickly grasped its significance and responded accordingly. Back in the office, three project managers were the glue that held the project together; first Kassie Hendy, then Eleanor Gardner, and now Sadie Mills. The project principal investigators have included myself, Kent Crippen, Austin Hendy, Betty Dunckel, and Shari Ellis, all of whom selflessly shared their passion and dedication to making the project a success. Several postdoctoral fellows, most notably Ronnie Leder and Jen Bauer, provided leadership and their knowledge. Likewise, many graduate students and undergraduate research assistants have contributed to the overall success of the project.

Thousands of others have ensured the success of the FOSSIL Project through their active participation in the CoP network. At the risk of excluding someone, several of our amateur colleagues have gone the extra yard. Linda McCall has been active in many ways. As our amateur liaison to the project team she sat through many hours of monthly meetings. Jack Kallmeyer of the Dry Dredgers Fossil Club in Cincinnati mobilized his club, promoted involvement, and has organized a mini-field conference (2016, Fig. 5) and sessions at professional meetings (like recently at the NAPC in Riverside, California). Lee Cone, in his capacity as President of the Special Friends of the Aurora Fossil Museum, mobilized engagement among his group to develop a citizen (community) science partnership with us and the Smithsonian Institution to search for rare early Miocene land mammals from the Belgrade Quarry in eastern North Carolina. I am very excited to see this latter project come to fruition as a jointly co-authored paper published in a peer-reviewed journal.

I also would like to recognize Gabe Santos of the Raymond Alf Museum (Webb School) in Claremont, California. He has used our myFOSSIL platform to engage his students and has promoted this to others; he recently had teachers from Mongolia uploading fossils using the app. I believe that all of these people and others have been advocates for the FOSSIL Project. They also have fundamentally helped to break down some of the perceived amateur—professional barriers that presented a challenge to us at the beginning of the project. To me, it mostly comes down to trust, good people, and working together for the common goal of advancing the science of paleontology and the love of fossil collecting. This is the road to success. To these folks and others who have contributed, we could not have done it without you.

The funding from NSF officially came to an end on 30 September 2019. Just as we launched the FOSSIL Project at NAPC 10 at the University of Florida in Gainesville in 2014, we recently closed the project’s organized professional activities at NAPC 11 at the University of California in Riverside, California in June of 2019 (Fig. 6). Many of the participants who were with us in 2014 also celebrated the FOSSIL Project at NAPC 11.

For years we have worked on a plan to sustain certain elements of the FOSSIL Project so that NSF’s investment and our hard work would be preserved into the future. The app will remain active, as will portions of our website. We will encourage the use of these components of the FOSSIL Project as we move forward. I also would like to acknowledge our four-year partnership with Atmosphere Apps of Gainesville, Florida–in particular Max Jones, project developer, and Eric Poirier, CEO. I have learned through them that web and app development is fundamentally a process of continuous iterative improvement. They have shared our passion and vision, and for this we are grateful. Using other sources of revenue, we plan to continue the maintenance and functionality of the app and certain components of the website—in particular the Groups, Members, eMuseum, and Resources, for a period of three years (until 2022). Our Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram social media presences will also continue at a level that will be dependent more upon your contributions. We hope, therefore, that you will feel empowered to continue contributing to the FOSSIL Project, and in so doing, sustain this robust community and network into the future.