Submitted by Stephen Godfrey, Calvert Marine Museum

Although peccaries resemble pigs, they actually occupy their own family — the Tayassuidae. They are artiodactyls (i.e., the even-toed ungulates), a large group of herbivores that includes pigs, hippopotamuses, camels, llamas, deer, giraffes, antelopes, sheep, goats and cattle. Remarkably, artiodactyls and whales (Cetacea) share a common ancestor as indicated by their DNA and anatomy. Consequently, they are grouped together into the Cetartiodactyla (from Cetacea + Artiodactyla).

Figure 1. The collared peccary (Pecari tajacu) lives in the southwestern United States, and south into Central and South America. They are also known as Javelina, i.e., “javelin” in reference to their fearsome canines (see Fig. 2), which they will click together to warn predator’s to steer clear. Peccaries are omnivores, so they will eat small animals, but they seem to prefer to feed on plants.

Image from: http://thepantanalsafari.blogspot.com/2014/02/invasive-species-threat-feral-pig.html

Like extant peccaries that live in social herds, their Miocene antecedents probably did likewise. Based on the number of peccary bones and teeth in the vertebrate fossil collection at the Calvert Marine Museum, Solomons, MD, they were amongst the most common land mammals living on the Atlantic Coastal Plain in Maryland during the Miocene epoch. Having said that, their remains are still very rare locally; which is why a recent discovery and donation to the museum is a very important addition to our collection.

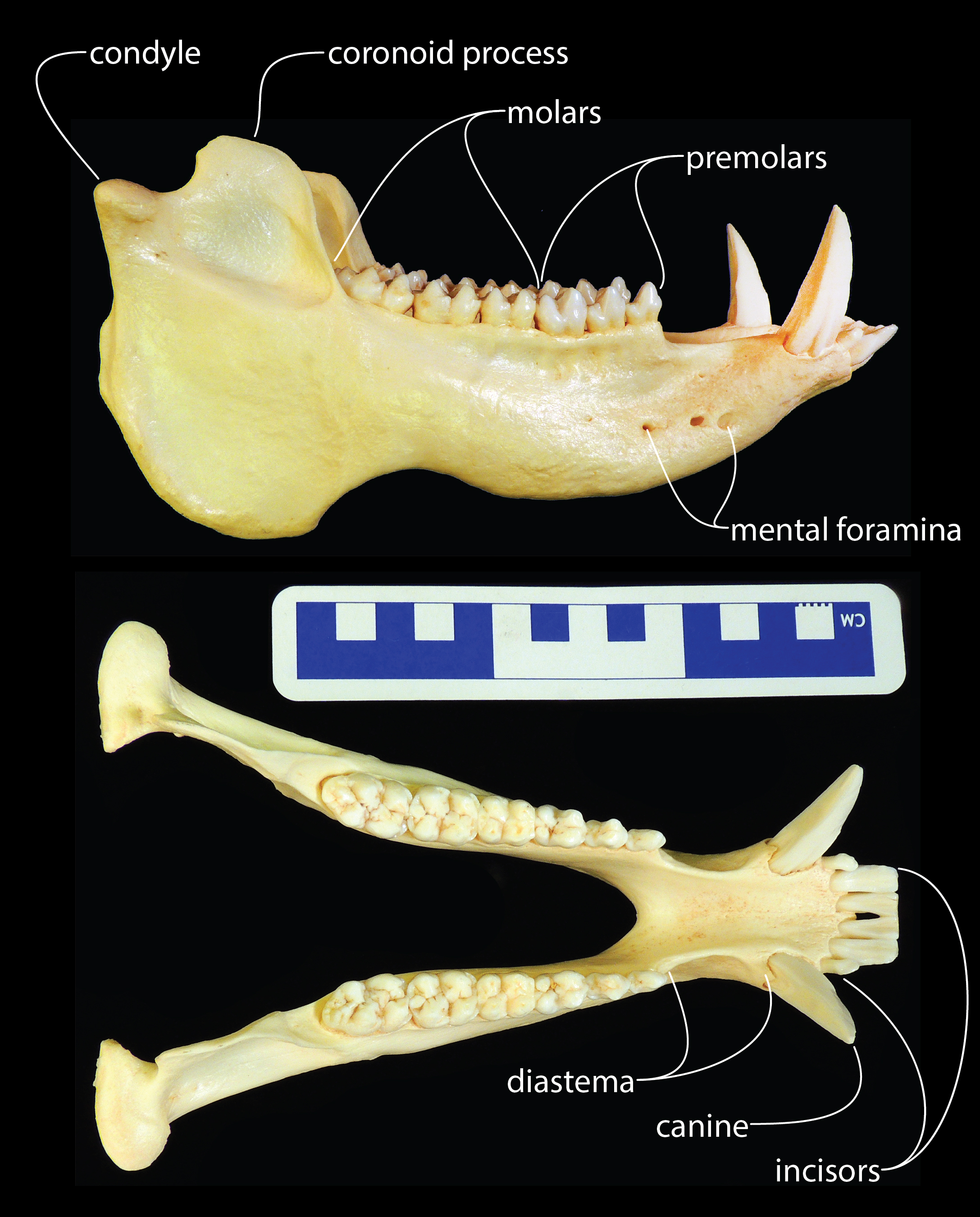

Figure 2. Lower jaw of a modern collared peccary (Pecari tajacu, Fig. 1) in right lateral and dorsal views respectively. Notice the large canines, which are missing in the fossil peccary jaw (Fig. 3) that was found along Calvert Cliffs. Like many species of mammals, peccaries have a wide diastema (literally, a long gap) as a normal feature, between its canines and premolars. Scale bar is in centimeters.

The peccary lower jaw, attributed to Dicotyles protervus Cope 1868, in Figure 3 was found by Mike Ellwood (a member of the Calvert Marine Museum Fossil Club) in a block of sediment that had fallen from Calvert Cliffs. When he first spotted this 14-15 million-year-old jaw, waves from an incoming tide were already pounding at it; a rescue excavation was initiated immediately. Although he was able to save most of the jaw, the Chesapeake Bay claimed several incisors. In spite of those losses, this is the most complete peccary jaw that has ever been found along Calvert Cliffs.

Figure 3. Mike Ellwood found this nearly complete lower jaw of the Miocene peccary, Dicotyles protervus Cope 1868. The right half of the lower jaw (i.e., a ramus) does not quite attach to the broken midline section of the left ramus. Notice also that the large lower canines (seen in the extant peccary shown in Fig. 2) and all but one incisor are missing, otherwise, this peccary jaw is the most complete one known from along Calvert Cliffs. Hands by K. Porecki, photos by S. Godfrey.

That the fossilized remains of peccaries are rare along the cliffs comes as no surprise. The sediments that comprise these naturally eroding sea cliffs were deposited in a marine setting, not the place one would expect to find peccaries. Bloat-and-float is the easiest way to imagine the carcasses of large terrestrial animals finding their way out into the Miocene Atlantic Ocean.

Peccaries originated in Europe during the Late Eocene epoch. From there, they made their way to all continents except Australia and Antarctica, but then they became extinct in the Old World sometime after the Miocene. About three million years ago peccaries first entered South America during what is known as the Great American Interchange when the Isthmus of Panama connected North and South America.