Sinking Our Teeth into Dinosaur Dentition

by Joy and Isabelle Churin

A couple of months ago, I decided to introduce my 8-year-old daughter to one of my most beloved movies as a child – the 1988 animated film The Land Before Time. We had a delightful time meeting Cera (a Triceratops), Ducky (a Parasaurolophus), and Littlefoot (an Apatosaurus). It has now become one of her favorite films, and it has sparked a fascination in dinosaurs and the prehistoric world. As a teacher (and proud parent!), I was more than happy to help stoke her eager curiosity by providing books, models, illustrations, as well as exploring websites (including the incredible myFOSSIL eMuseum) alongside her. We even have plans to visit a few natural history museums this year!

My daughter is a visual learner, and she enjoys diagrams and infographics. In our search, we discovered an infographic on dinosaur teeth by Main Street Smiles that she found particularly enriching. It visualizes the colossal scale and variety of dinosaur teeth while also providing fascinating tidbits on the dental qualities, diets, and jaws of these awe-inspiring creatures. Check it out below:

As you can see, the infographic is packed with bite-sized trivia on dinosaur teeth (with the Megalodon, Saber-Toothed Tiger, and Woolly Mammoth included for good measure). We wanted to share some more compelling dino dentistry facts that we discovered during our “excavation” on the web.

What Dinosaur Had the Largest Teeth?

The “king” of dinosaurs, Tyrannosaurus rex, holds the record for the longest tooth at 12 inches. T. rex had up to 60 thick, serrated, and conical teeth that would be replaced after breakage and damage. The colossal size and immense strength of T. rex teeth meant that the replacement process took about 2 years. In fact, all species of dinosaurs could regrow teeth at varying rates! Herbivore dinosaurs like the Triceratops, Parasaurolophus, and Apatosaurus (our friends from The Land Before Time) are believed to have been able to regrow teeth quickly because of the extensive wear and tear caused by stripping and grinding plant material. However, recent research has shown that some carnivorous dinosaur species like the Majungasaurus may have regrown new teeth roughly two to thirteen times faster than other carnivores, similar to the rate of modern day sharks (every two months)!

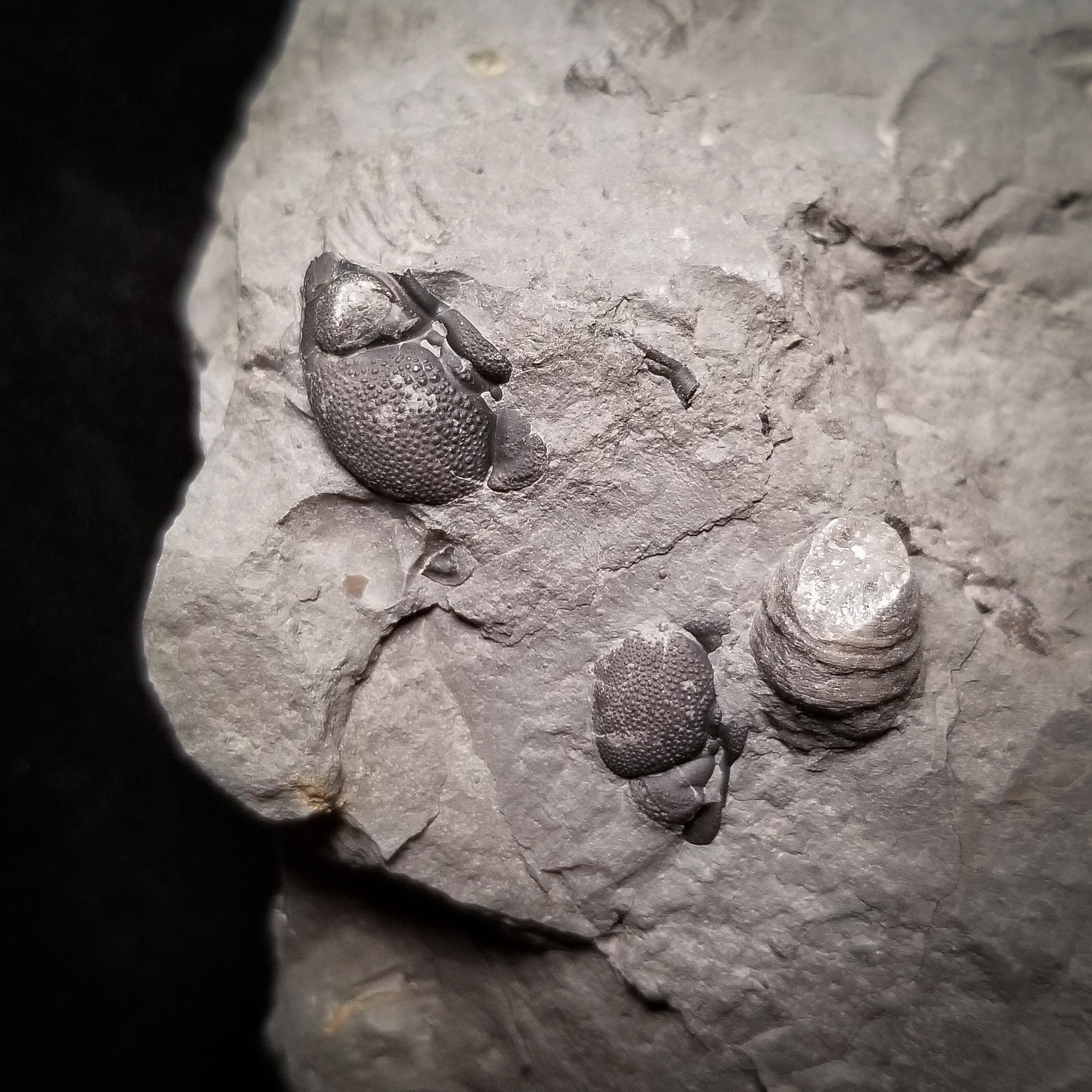

Majungasaurus

What Prehistoric Creature Had the Greatest Bite Force?

The Tyrannosaurus rex had the most powerful bite out of any terrestrial animal. Incredible technology has enabled paleontologists to determine the approximate bite force by constructing a three-dimensional digital model of the T. rex skull using anatomical knowledge of birds and crocodiles. The results were astonishing! A T. rex could bite down with the force of 12,800 pounds, about as much as an adult T. rex weighs (or an elephant). Imagine 13 grand pianos slamming down on you! However, the sea-dwelling monster known as C. megalodon puts T. rex to shame with a staggering bite force of 41,000 pounds! It could open its jaw 6 feet wide and 7 feet tall, effortlessly chomping down on prey like dolphins, whales, and other sharks.

Why Should You Embrace Your Child’s Fascination With Dinosaurs?

As a closing note, I wanted to touch upon why I am so eager to encourage my daughter to explore the fascinating field of paleontology. Here are some of the qualities that children can develop through a giddy enthusiasm for dinosaurs:

- Critical thinking abilities.

- An understanding and respect for the scientific process.

- Creativity and imagination as they draw these magnificent creatures of the past, and engage in pretend play.

- Curiosity stimulates the growing brain to be ready for learning and information retention.

- Conceptual fields like dinosaurs cannot be passively absorbed. This urges children to read books, ask questions, and engage in learning. Persistence and information-processing skills are cultivated through the quest for knowledge.

- Dinosaur and prehistoric names are challenging – so they develop verbal and writing skills!

- Confidence! When children unearth the answers they seek, they will feel more capable and prepared to take on more complex problems.

- Dinosaurs help children learn about classification. Dinosaurs have sub-categories (plant eater, meat eater, etc.), so children develop systematic thinking and organization skills.

- Ignites a passion for STEM fields in both girls and boys! Equality in these fields benefits the greater good.

Thank you so much for reading! We hope you enjoyed the infographic, the fun (and terrifying) facts, and the inspiration for encouraging children to embrace their latest fascinations, especially in conceptual topics like dinosaurs and the prehistoric world.